Gratitude: More than just “thinking positive”

Practices (like gratitude) originating in positive psychology have been flooding the mainstream for almost two decades, and for good reason. At its core, applied positive psychology aims to increase the frequency of positive experiences and emotions – and who doesn’t want that? But the science behind these practices suggest that it’s much more than just “thinking positive.”

In a study conducted at University of Southern California (Fox, Kaplan, Damasio, & Damasio, 2015), a team of researchers observed the brain activity of those in a grateful state of mind. They noticed increases in activity in two regions: the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). These two areas are both linked with important brain functions such as the processing of emotions, interpersonal relationship building, fulfilling social interactions, moral judgment, and the ability to understand the mental states of others. All of these functions work together to help us build strong relationships, make sound decisions, and monitor emotions – all critical skills for effective workplace functioning.

They also noted the unique impact that gratitude has on our brains, “A lot of people conflate gratitude with the simple emotion of receiving a nice thing. What we found was something a little more interesting. The pattern of [brain] activity we see shows that gratitude is a complex social emotion that is really built around how others seek to benefit us” (Hoffman, 2015).

Why do we need gratitude now?

The current rise in popularity of positive psychology practices is no accident, either. Overwhelming demands for increases in workplace productivity and decreases in satisfaction with decision-making have led to exhaustion, burnout, and eventually mental health difficulties (Colligan and Higgins, 2006). Burnout consists of feelings related to emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). If you’re thinking, “Well that’s important to avoid, but it’s not like we’re talking life or death here,” think again. In medical settings, research has linked burnout to such critical outcomes as patient mortality (Aiken, Clarke, Sloan, et al., 2002). Positive psychology practices, such as Three Good Things by Martin Seligman and his colleagues, have been shown to reduce workplace burnout and depression, decrease the number of employee errors, and increase the quality of workplace outcomes (Seligman et al., 2005).

How do I do it?

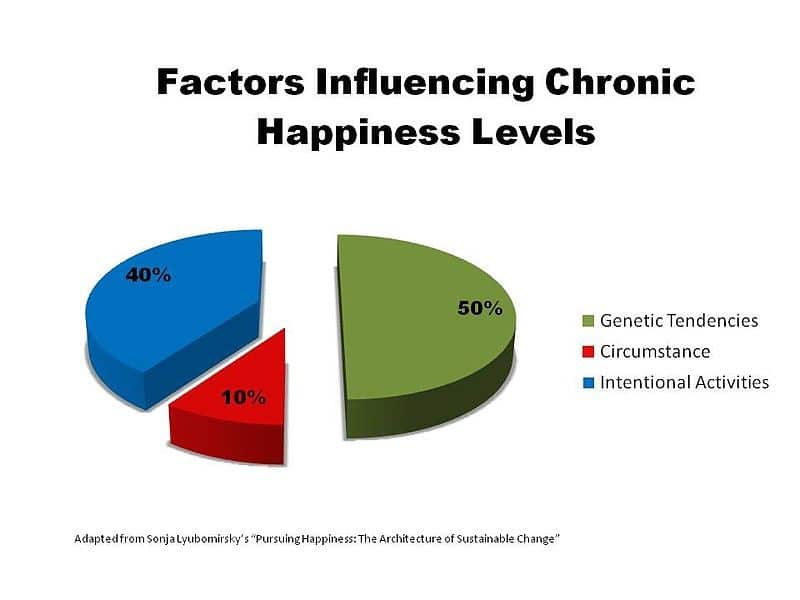

Perhaps one of the most exciting parts of gratitude research is that anyone can put it into practice; all it takes is a little intentionality. The Three Good Things (3GT) exercise (Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005) was developed to help individuals take notice of and focus on the good in their lives. Further, individuals have a tendency to spend more time thinking about what is bad in life than what is helpful. Worse, focusing on bad events increases one’s likelihood of experiencing anxiety and depression (Seligman et al., 2005). A recent study showed that individuals diagnosed with clinical depression displayed significantly lower gratitude (almost 50% less) than those without depression. The 3GT exercise requires individuals to record, every day, three good things that happened to them each and why those good things occurred. The intervention is targeted to increase happiness rather than to decrease suffering. In fact, research suggests that journaling your gratitude for just five minutes each day can have lasting effects on your well-being, with increases in happiness up to 25% (Emmons, 2008). In previous studies, participants have reported increased levels of happiness, decreased experience of stress, sadness, and exhaustion, and better outcomes for patients and coworkers.

Start right now: What are your 3GT for today?

By: Jennifer Morton, M.A. & Taylor Montgomery, M.S.